By Mike Fitz

Fat Bear Week is over for another year, and Holly has claimed the title of the fattest bear of 2019. She is a true champion of Katmai National Park, an individual who exemplifies skill and success in the bear world. In Katmai, fully grown and well fed adult female bears like Holly can often tip the scales at 600-700 pounds and Holly is probably well within, or even exceeds, that weight class. Based on her overall size though, how might she compare to other bears in Katmai? And just how big can a Katmai bear grow? Now, thanks to unusual use of terrestrial laser scanning technology, we have some answers.

Holly is the reigning queen of fat bears. She was voted the fattest bear of 2019 in Katmai National Park’s annual Fat Bear Week tournament.

The size and weight of wild bears has always been problematic to measure. You can’t just walk up to a bear with a tape measure and tell it to hold still or expect it to stand on a scale. Hunter-killed bears can provide some info, but the “record” bears documented by the Boone and Crockett Club are ranked on skull size, not body mass. Biologists will sometimes weigh and measure wild bears as part of their studies, yet this requires tracking and tranquilizing animals. While the methods and procedures used to tranquilize bears are well tested and reliable, biologists cannot eliminate all risk to themselves or the animals. Therefore, the application of non-invasive technology may provide ways for people to satisfy their curiosity and learn more about wildlife without interacting or harming them.

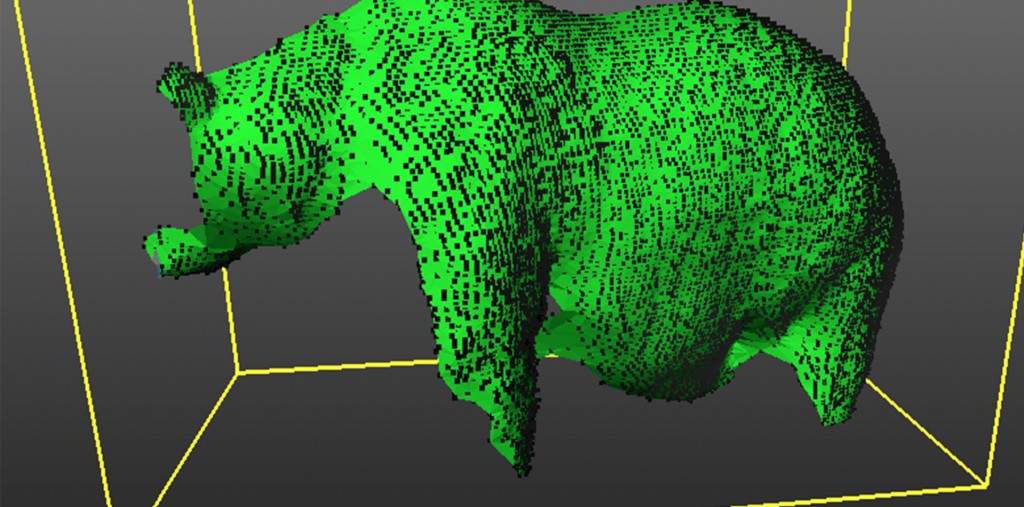

Similar to echolocation used by bats, terrestrial laser scanning technology sends out a series of laser beams that “echo” off an object. The returning signal is recorded by the scanner. Specialized computer software is then used to render a three-dimensional computer model of the object or place. The process is frequently used by civil engineers, GIS specialists, and surveyors to document, analyze, and monitor roadways, gravel pits, mining sites, and buildings. The scanning technology also determines an object’s volume very precisely without the need for a person to physically measure it, which brings me back to bears.

In their effort to gain as much fat as they can before winter hibernation, dozens of bears have come to rely on Brook Falls as a place where they can wait for salmon to come to them. Experienced and skilled bears know patience is the key to success at the falls. By sitting or standing and waiting for salmon to come to them, they can make a huge profit in calories without expending much energy.

Because terrestrial laser scanners need to record thousands and sometimes millions of data points to achieve a reliably accurate rendering of a subject or landscape, the object of interest needs to remain stationary. Where might wild bears remain still long enough to complete an accurate scan? Brooks Falls.

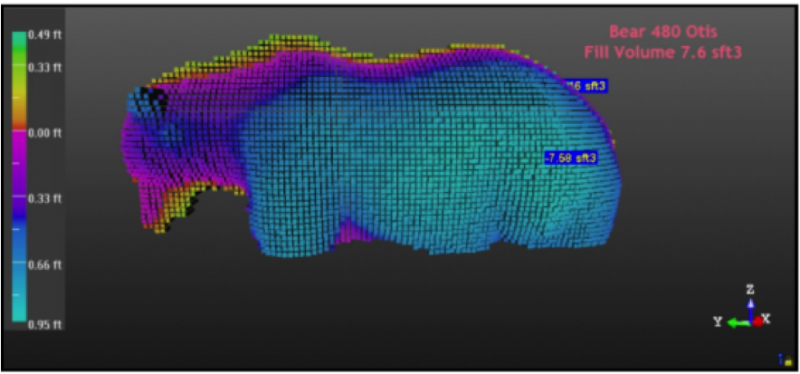

On September 16, Joel Cusick, a geographic information specialist with the National Park Service’s Alaska Regional Office, set up a Trimble SX10 scanner on the elevated wildlife-viewing platform adjacent to Brooks Falls. He then waited for good opportunities to scan bears fishing there. Good opportunities came when a bear stood still and did not have a significant portion of its body submerged in the water. To get an accurate scan, a bear had to remain stationary for about 16 seconds.

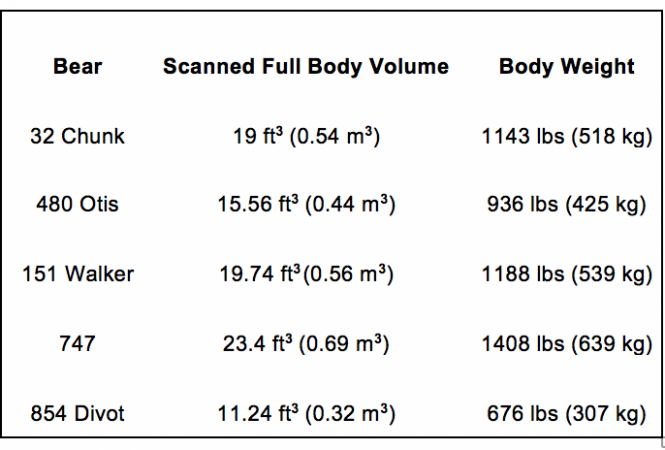

Five bears stood still long enough—32 Chunk, 151 Walker, 480 Otis, 747, and 854 Divot. Two bears, Otis and Walker, were scanned more than once from different locations, which allowed Joel to combine the scan data for a more accurate model of the bear. Other bears were present as well but were too obscured by water or did not remain still long enough to get an accurate scan.

On the computer afterward, Joel processed the scans to exclude nearby objects like rocks. Since the scanner only saw the bear from one side, it only recorded half a bear’s volume. Once the images were cleaned of non-bear objects, the animals’ true volumes were calculated by doubling the original value. (Of course, this presumes that bears are completely symmetrical. They are some irregularities, but I don’t think Otis’ floppy ear or any other asymmetry would make a significant difference.)

Spread over 1.5 hours, Otis occupied nearly the same position at the falls, which allowed his volume to be determined with high precision.

Although volume isn’t the same as mass, it’s somewhat easy to calculate an object’s mass when you know its volume and what it is made of since mass is a product of density and volume. In other words, just multiply an object’s density by its volume and you are left with its mass. With bears, the math is complicated slightly by the fact that bears aren’t made of only one type of tissue. Like our own bodies, they are a combination of water, muscle, bone, organs, and especially at this time of the year, fat. Because the bears at Brooks Falls were not physically handled, only estimates of their body composition were used to calculate their mass.

Brown bears in this area are often around 35% body fat in late summer and fall. For simplicity, the rest of the bear was considered to be the lean tissue, which is about the density of water. With the math complete, we now have a good idea of what the bears weighed on the day of the scans. The 2019 Fat Bear Week tournament was full of truly fat bears.

Wow.

These statistics illustrate that Katmai’s bears are some of the biggest in the world. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, where bears have to work much harder to find nutritious food, adult females average 296 pounds and adult males average 457 pounds during September and October. Even 854 Divot, a mature female who is not particularly large compared to Katmai’s adult males, is almost 700 pounds. I’ve long thought 747 was a very big bear, frequently stating that he’s the largest I’ve ever seen and that he might weigh 1,200 pounds. Now, I know that was likely an underestimate! As Katmai National Park posted on their Facebook page, 747’s volume on September 16 was about the size of a side-by-side refrigerator. At over 1,400 pounds, he’s probably larger than 99% of all brown bears, and he might be within a couple hundred pounds of the biggest wild brown bear ever recorded.

When I corresponded with Joel Cusick, he was careful to note that while the weights are impressive, it’s the volume measure that is more accurate since the bear’s body composition could only be estimated. The test project also lacked a control. To ensure its accuracy, it would need to be used on bears from a captive facility where researchers can physically measure and weigh the bears to compare the results with those of the laser scans. Even so, the scans from the falls provide us with a reasonable estimate of their weight, perhaps even within 50 pounds.

This is the first ever application of terrestrial laser scanning technology on wildlife. When we apply technology in an unconventional way, we might be able to better satisfy our curiosity. More importantly, we might be able to track the growth of bears at Brooks Falls without the risks associated with drugging and handling them. That information could be coupled with salmon escapement numbers or an individual bears’ fishing success to more fully understand the factors that influence their summertime growth. Like watching wildlife through a webcam, it could allow us to learn more about them without disturbing or altering an animal’s behavior. Perhaps one day, we’ll be able to do more than just guess how much bears like 747 or Holly weigh in June, July, and September. We’ll be able to follow their growth from skinny to fat with precision.