By Mike Fitz

Watching bearcam, it’s easy to think of Brooks River as a place primarily for bears, yet the river and its bears do not exist in a vacuum. They live and survive in the most visited place in Katmai National Park.

On Thursday, July 25 at 10 a.m. Pacific (1 p.m. EDT), I hope you’ll join me in the comments for explore.org’s Brooks Live Chat channel for a written discussion about bears and people at Brooks River. It’ll be a real-time conversation on the history of Brooks Camp, bear activity and management at Brooks Camp, the meaning of national parks, and the future of Brooks River.

I’ll be joined by Naomi Boak, a current ranger at Brooks Camp with the Katmai Conservancy, and Jeanne Roy, a former district interpreter for Katmai National Park. Part of Naomi’s job this summer is to staff the bridge and platforms at Brooks River so she can help provide a perspective on the opportunities and challenges of that job. Jeanne Roy is now a volunteer moderator in the bearcam chats and has an extensive knowledge of Brooks Camp history and bear management.

Below you’ll find a very brief primer on the history of Brooks Camp, the National Park idea in the United States, and questions for you to contemplate for the conversation.

A Very Short History of Modern Brooks Camp

Katmai National Monument was established in 1918 to protect the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and the area devastated by the 1912 Novarupta-Katmai eruption, the largest of the 20th century and fifth largest in recorded history. Although the Brooks River area was not included in the original monument boundaries, explorers who came after the 1912 eruption noted area’s potential wildlife values, especially bears. In 1931, the monument was nearly doubled in size “for the protection of the brown bear, moose, and other wild animals,” and included the Brooks River area. The monument boundaries were further adjusted by other presidential proclamations. In 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) set Katmai’s current boundaries and changed its designation to a national park.

The agency tasked with managing the monument, the National Park Service (NPS), tried to secure funding for a ranger at Katmai but was unsuccessful for many decades after the 1918 proclamation. Only three NPS employees had visited the monument before the NPS issued a concession permit for Brooks Lodge, which opened for business in 1950 at the mouth of Brooks River. Along with the lodge, Katmai’s first ranger arrived that summer.

The original Brooks Lodge was very small and catered primarily to anglers. Beginning in the 1960s, especially after the development of a road leading from Brooks Camp to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, more and more people other than anglers began to visit. This trend continues today. While fishing remains a popular activity, bear viewing and photography have superseded fishing and are by far the most popular activities at Brooks Camp. The significances of parks and how we utilize them change over time. This is a common thread in the history of national parks. Why are Katmai and Brooks River significant to you?

Bear Activity at Brooks River

No one knows how many bears lived within the boundaries of Katmai National Monument in the early to mid 1900s, but the population was likely much lower than today due to hunting, fewer salmon in the Naknek River watershed, and the impacts of the 1912 Novarupta-Katmai eruption. Since long before the monument’s establishment, Katmai’s bears have occupied people’s minds, but so few bears used Brooks River in the 1950s that seeing one or even their tracks was a notable event.

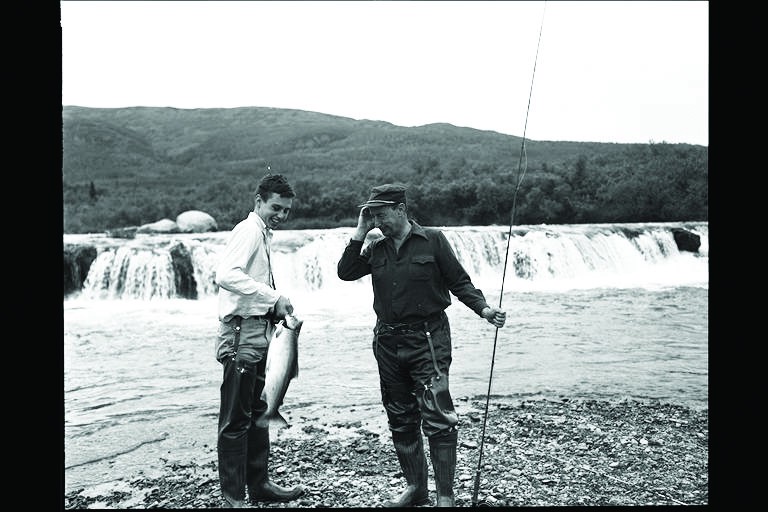

While it seems almost unthinkable today to fish at Brooks Falls in July, so few bears used Brooks River in the 1950s that people often fished and picnicked there. Shown here are Adlai Stevenson and his son John Fell Stevenson.

In the late 20th century, greater protections for brown bears (hunting for example was not permitted in the national monument) likely led to steady increases in the bear population of Katmai and the Alaska Peninsula. By the 1970s, a few bears fished Brooks River in July but 20–30 bears regularly used the river in late summer and fall. The numbers of bears using the river continued to grow through the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Last year, Katmai’s bear monitoring staff observed 62 different bears regularly using Brooks River.

Brooks Camp now operates differently and on a much different scale compared to the 1950s and 1960s. Park rangers are continually challenged to manage people and wildlife where both are funneled into the same small area. Can a place like Brooks Camp adapt the changing needs of people? Should we expect bears and wildlife to adapt to the presence of people in national parks? What consequences does that have for our own visits?

A Few Rules

The increase in bear numbers at Brooks River has led to a changing suite of rules. We often think of park regulations as something intended for human safety, but many, if not most, rules and regulations are written primarily to protect park resources, especially in the case of Brooks Camp. Katmai’s laws and policies page includes links to the most pertinent rules for Brooks River. Wildlife distance regulations, seasonal area closures, and special rules regarding food, property, and fishing within an administrative area called the Brooks Camp Developed Area help to govern our behavior at one of the most famous bear-watching areas in the world. We’ll discuss what’s allowed, what’s not allowed, and give you the opportunity to ask questions about the regulations regarding Brooks Camp.

The National Park Service Mission and the Meaning of Parks

When Congress passed the 1916 Organic Act establishing the National Park Service, it also created a mission for the fledgling agency: “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Whole books have been written on the meanings, significance, and consequences of this mandate, which can seem quite contradictory at times. Many parks, including Katmai, have struggled with this conundrum. How do you balance access and enjoyment with the needs of wildlife and the protection of park resources?

The Future of Brooks Camp

The future of Katmai and Brooks River might look like a lot of other national parks. Climate change will influence the flora and fauna. People will continue to visit and likely in increasing numbers. These are foreseeable, long-standing, and predictable issues, so should we mitigate them?

Katmai’s significances and the ways people use this place have changed over time. Should we embrace changing values for the importance of national parks or let historical precedence take priority? What choices should we make to help the National Park Service meet its mission of providing for visitor enjoyment while at the same time conserving the scenery, natural and historic objects, and wildlife for future generations?

The Bear-Watching Experience

I’ve thought a lot about how to reduce my potential impact on bears when I visit Brooks River. I’ve often emphasized the importance of giving bears space, not only for our own safety but for the welfare of the bears. Often, it is necessary to make personal decisions that go beyond the rules. Ethical visitation in bear country requires people to be closely attuned to bear behavior and to watch for subtle signs of stress, such as a yawn or the bear changing its intended travel path. So what might the best practices for bear viewing at Brooks River look like? What about those of us who watch the bearcams yet don’t visit? How might you help protect bears, salmon, and Katmai?

One of the beautiful things about the bearcams is that it is accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Through the cams we can experience the abundance of Katmai and consider the challenges of protecting it. We may never be able to fully answer, “How can we best protect and enjoy Brooks River?” But, we can certainly talk about it. Please join the conversation in the comments for explore.org’s Brooks Live Chat channel on Thursday, July 25 at 10 a.m. Pacific (1 p.m. EDT).