By: Mike Fitz

When I arrived in Churchill, Manitoba, it was immediately apparent that polar bears were to be taken seriously. Guidelines emphasized not walking alone and especially not after 10 p.m. Nearly every place of business posted signs with the phone number of Polar Bear Alert, the town and province’s program to monitor and, if necessary, haze bears away from the community. At the airport, a warning sign hung prominently near the baggage carousel.

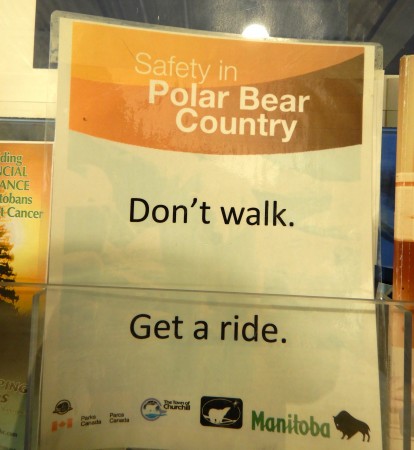

This sign at the Churchill Airport informs newly arrived persons about how to stay safe in polar bear habitat.

Reading it, I could hardly wait to look for bears.

Churchill, Manitoba, the self-proclaimed “Polar Bear Capital of the World,” lies over 600 miles north of Winnipeg along the western shore of Hudson Bay. Around 900 residents live in Churchill and no roads connect it to any other town. The nearest sizeable community is Thompson, about 250 miles south. It occupies a rich transition zone of ecosystems. Here—where boreal forest, arctic tundra, and the Arctic Ocean meet—trees are slow growing and often stunted by cold, damp soils or flagged by the pruning action of wind-driven snow and ice. Marshes, bogs, and shallow ponds are common and permafrost underlies much of the landscape.

Polar bears are the town’s most famous and popular attraction. Each fall, Churchill provides a rare, predictable opportunity to watch polar bears and thousands of tourists flock here to see them. The confluence of bears and people in this remote community has created a special set of challenges, which can only be met through the town’s willingness to tolerate the largest four-legged predator on Earth.

To understand why Churchill is known for bears, we need only understand a bear’s motivation to find food. When your life revolves around eating a year’s worth of food in five to eight months, then hunger is a powerful motivator. Brown and black bears, for example, hibernate through winter, sometimes losing a third of their body weight during that time. They utilize the late summer and fall seasons to gorge and gain the fat necessary to sustain them through the winter fast.

Polar bears in western Hudson Bay, as part of one of the most southerly populations of polar bears on Earth, must endure an ice-free period each year when, like a hibernating brown bear, they lose a significant amount of weight. Unlike black and brown bears though, which are omnivorous, polar bears are sea ice specialists and highly carnivorous. In summer and early fall the bears in western and southern Hudson Bay hover on land, surviving on their fat reserves while they wait for sea ice to form again. On land, polar bears have been observed eating kelp, berries, goose eggs, and other foods, but their digestive system and metabolism are not well adapted to a terrestrial diet. Winter and spring are the most important seasons for them to get fat. Polar bears use sea ice as a platform to hunt seals, their preferred and most important prey. Their physiology is so well adapted to digesting seal blubber that some scientists refer to polar bears as “lipivores,” a specialized carnivore adapted to surviving on a diet high in fat.

Due to a quirk of topography, the Churchill area provides polar bears early access to sea ice. Located along an east-west trending bight and with an influx of fresh water from Churchill River, the area is generally one of the first places in western Hudson Bay where sea ice forms. A slow counter-clockwise current also circulates in the bay, which brings the last of the area’s sea ice toward shore along the Ontario-Manitoba border. Consequently, bears can find ice here longer than most other places in Hudson Bay. Inland from the shoreline, the area is also important to expectant mother bears who build maternity dens in the forest. There, they give birth and nurse newborn cubs until the cubs are strong enough to follow their mothers onto the sea ice. For these mother bears, the period of fasting is incredibly long, sometimes extending eight months!

For these reasons, Churchill is perhaps the only place where large scale polar bear tourism is possible. It’s located where bears gather predictably in the fall and it has the infrastructure to support polar bear based tourism. Tourists can reach Churchill through a rail line and airport and they can view the bears on the tundra through specialized “tundra buggies,” custom built vehicles resembling a box-shaped bus with monster truck tires. Thousands of people visit the town each fall to watch bears before they depart onto sea ice. But, it wasn’t always this way and polar bears weren’t always considered an asset here.

A large male polar bear walks on the shore of Hudson Bay while a tundra buggy full of tourists lurks in the background.

Tundra buggies are specially customized vehicles to seek out polar bears on the tundra east of town.

People and polar bears have encountered each other in the Churchill region as long as they’ve both occupied the area, a time span extending at least four thousand years into the past, but the story of the town’s modern day relationship with bears begins in the 1940s when, in 1942, the United States established a military base in Churchill, initially bringing nearly three thousand officers and enlisted men. At first, polar bears weren’t much of an issue around the base. However, bears soon learned to scavenge food at open dumps and trash pits.

For bears, garbage is an especially attractive source of food. Bears don’t have to work hard to find it, people never stop producing it, and it’s high in calories. During the middle of the twentieth century, many of Churchill’s bears became increasingly attracted to trash and bears were frequently seen scavenging for food at the town dump. Mothers taught their cubs to feed on garbage, extending the bears’ reliance on it across generations. It’s also easy for bears to recognize that people are the source of the larder—if food can be found at a dump then it can be found near people’s homes as well.

“In Churchill, these bears have been on the shore since July and most of them haven’t had food. Most of them have been losing weight all summer, about one to two kilograms per day in body weight, so they’re hungry,” says Geoff York, senior director of conservation for Polar Bears International. Geoff and I drove around the town late one morning to discuss how the community has learned to co-exist with its bears. Like so many other places where bears and people come into conflict, the story and the attempt to protect people and wildlife revolves around food. In late summer and fall, Geoff remarked that polar bears “are ready to go out and find some food. That’s going to affect their behavior, their risk making decisions, and it makes them less predictable around people.”

When bears in Churchill actively sought and received food from people, it led to maulings, high rates of property damage, and many dead bears. During in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, twenty to thirty polar bears were often killed in the Churchill area per year. Twenty-nine bears died in 1976, most of whom were shot by residents and conservation officers as they encroached on town. In 1983, referred to as “the worst year ever” by Edward Struzik in his book Arctic Icons, three people were mauled and over thirty bears were shot in Churchill. At the same time, polar bear tourism began to spike. It was clear to nearly everyone that the continuing trend of bear-human conflict was unsustainable for the bears, the community, and the growing bear-watching industry.

Shooting the bear “used to be the answer,” says York. “A bear came around the community, it was often killed or removed from the population. Now we understand that’s not the best idea if you want to conserve these amazing bears.”

In the 1970s, Manitoba began to hire biologists and conservation officers to study and manage polar bears in the Churchill area. The effort eventually led to the creation of Polar Bear Alert, a staff dedicated to patrolling and, if necessary, hazing, capturing, and removing bears from the town. The program represents a significant investment from the province, according to York.

“Highly trained people are constantly on patrol here to intercept bears ideally before they get too close to town if not to escort bears through town safely or if needed use aversive conditioning. They went from killing upwards of twenty-plus bears a year to now it’s rare that a single bear is killed in conflict so there’s clear benefit of that investment.”

Polar Bear Alert’s hands-on hazing, capturing, and removal of polar bears is well publicized and attracts the bulk of the media coverage about Churchill’s bear management. It’s easy to understand why; its optics are unique. During the ice-free season, it is not uncommon to see conservation officers speeding away to intercept a bear that is approaching town then hear the report of exploding cracker shells (one of the non-lethal deterrents used to scare bears away from the community). Sometimes bears are tranquilized or captured and taken to a holding facility, the “polar bear jail,” where they are kept until sufficient sea ice forms or the jail reaches capacity (whichever comes first). When released, bears are coaxed into culvert traps then taken to the edge of the bay or tranquilized and airlifted away from the town. Once on the ice where they can find food, bears are unlikely to return that season.

What often gets lost or ignored in stories about Polar Bear Alert, however, is the collective action of Churchill’s citizens to minimize bear-human conflict, something arguably more important than guns-blazing active management of bears. Even Polar Bear Alert’s website makes the distinction clear: “The Polar Bear Alert Program begins with changing people’s behaviour, not aggressive handling of bears.” People respect the bears and protect them by minimizing their access to trash, avoiding areas where bears might lurk, and developing infrastructure that prevents bear-human conflict.

Many communities struggle to keep bears away from garbage. In Churchill today, however, bears have almost no access to trash. Weaning bears off of garbage was one of the most important and successful measures implemented in the community. At first, trash was buried at the dump, but this didn’t eliminate the bears access to it as trash was still left on the ground for long periods of time. Incinerating trash was also considered, but this option was eventually rejected due to cost. Trash is now secured in an “Alcatraz of garbage“ until it can be safely buried within a locked and fenced-in area. In town, garbage is collected only on certain streets on specific days and after working hours begin in the morning. This reduces the amount of trash outside and the duration it is unsecured.

In Churchill, trash is secured within a modified shipping and receiving building from the abandoned military base.

Like Brooks Camp in Katmai National Park, where thousands of people go to watch brown bears fishing for salmon, Churchill’s location attracts bears through and near it, and the town’s infrastructure wasn’t initially designed to reduce conflict between bears and people. Now, however, the community is trying to adapt where it can. Churchill combined its hospital, school, and community center into one large interconnected complex. Here, people can gather, learn, and play without having to travel outside from one building to another. This is welcome when temperatures reach -40˚F, but it is also an important design to reduce bear-human conflict. In the community center, children can play in an indoor playground and patrons can access a library. For exercise, there is a basketball/volleyball gym, hockey rink, curling rink, and weight-lifting facilities. It also offers a space just to relax. The last couple of days in town, I went to the community center and sat with my binoculars at a large window opening to a view of the bay where I could safely look for bears.

While bears are no longer conditioned to seek garbage, the continued close proximity of bears and people is not without risk. There are no regulations that limit where you can go on foot in Churchill either. Over time, and sadly because people were mauled by bears within the town, the community has adopted an informal set of guidelines to reduce the risk of a close encounter with bears. Walking alone through town, especially at night or through areas with limited visibility, is discouraged. Taxi service is easily available and polar bear tours often provide shuttle services for their clients.

I asked Geoff York what else Churchill could do to reduce the potential for conflict, since bears wander through the community during the ice-free season. Along with increasing access to bear-resistant trash containers and perhaps installing additional street lighting, Geoff recommends making deterrents like bear spray more accessible.

“The lowest hanging fruit on that tree is bear spray. For those of us who live and work in bear country and the western mountain states, bear spray is super common. It’s super uncommon in the north. Part of it is just accessibility. It’s a hazardous material to ship so getting it to places by plane in difficult. Another big part of that is just getting people the information to see so they’re comfortable that it works on polar bears, which it definitely does. Like any deterrent, it’s not perfect, but it’s a great tool to have in the tool box.”

During my stay in Churchill, I was loaned a canister of bear spray and I was glad to have it, even though I did little walking through the town and I never saw a bear while I was on foot. Bear spray is easy to use, highly effective, and, unlike a firearm, it is non-lethal. In Churchill’s arctic climate though, I had to take extra precautions to make sure it stayed warm and easy to reach during cold air temperatures. If the canister became too cold, then it may not discharge properly, so I was sure to keep it tucked in an easily accessible place within my parka. I also wore mittens that allowed me to expose my fingers quickly without removing my gloves in case I needed extra dexterity handling the canister.

As darkness fell in the late afternoon—sunset in Churchill happens before 5 p.m. in mid November—I was extra cautious. Even though there was enough ambient light from streetlights to see where I was going, I used a headlamp. Polar bears blend into white snow quite well, obviously, so while the headlamp wouldn’t necessarily help me see them better, it would help me see their eye shine (bears have eye shine like many carnivores). If I have the opportunity to go back, I would also consider carrying a flashlight with an extremely bright strobe setting, as the strobe could be disorienting to bears. If the use of non-lethal deterrents like bear spray become ingrained in the community’s culture, much like not walking alone late at night, then both people and bears will become even safer.

Perhaps Churchill isn’t ideal habitat for everyone, but I spoke to a lot of people who love it there and are willing to do what they can to protect bears. They’ll probably have to work even harder in the near future too. Climate change poses a new challenge for Churchill’s residents by increasing the duration of Hudson Bay’s ice-free period, forcing bears to spend longer periods of time on land and increasing the potential for bear-human conflict. As a result, arctic communities across Canada and Alaska are now dealing with polar bears at unprecedented levels.

As Churchill proves though, coexisting with wildlife is possible when a community collectively values the animals. For this remote town on the edge of Hudson Bay, learning to live with bears—meeting the challenge—wasn’t quick nor easy nor did it happen without a bit of self-imposed sacrifice, but the effort is an acknowledgement of respect and value for the animals. It offers an example that can be utilized by other communities that share habitat with bears. While “polar bear capital of the world” is self-proclaimed, the town’s efforts to reduce bear-human conflict have earned it the right to keep the moniker.