by Mike Fitz

Across their worldwide range, from Europe to Alaska to the Rocky Mountains, brown bears live as omnivores. They have one of the most diverse diets of any mammal species and plants form the bulk of their diet in many ecosystems. Even Katmai’s bears, famous for fishing habits, utilize plants for energy and nutrition throughout much of the spring and summer. Despite the reliance on plant foods, however, their digestive tract remains largely that of a carnivore, unable to digest and extract much energy from coarse plant foods–a constraint on their lifestyle that is tied to their evolutionary legacy.

Similarly, the ways in which people use Brooks Camp are also tied to its past. The development of facilities at the river and an increase in visitation over the last several decades has created many situations in which people and bears often come into close contact. Many bearcam viewers commonly wonder, what is permitted at Brooks Camp and how might we reduce our potential impacts on brown bears?

In this post, I hope to provide some insight into those questions. Importantly I want to further the conversation about bear and human interactions at Brooks Camp and provide some context on how it became a world-famous bear viewing destination. At the bottom of the post, you have the opportunity to comment, ask questions, and express your concerns. Let’s avoid posting photos or videos of instances you think were rule violations, but it is OK to describe situations if that helps me answer your question. Throughout the rest of the bearcam season, this can serve as a running conversation on the history, management, and legacy of the changing dynamic between bears and people at Brooks River.

A Very Short History of Brooks Camp

The human history of Brooks River begins nearly 5,000 years ago when people first established campsites here to hunt large animals like caribou. Since then Brooks River has become one of the most continuously occupied places in Alaska.

Katmai National Monument was established in 1918 to protect the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and the area devastated by the 1912 Novarupta-Katmai eruption, the largest of the 20th century and fifth largest in recorded history. Although the Brooks River area was not included in the original monument boundaries, explorers who came after the 1912 eruption noted area’s potential wildlife values, especially bears. The monument was nearly doubled in size in 1931 “for the protection of the brown bear, moose, and other wild animals,” and included the Brooks River area. The 1931 proclamation did not mention Alaska Native residents or include any provisions that allowed for their continued use of the area, even though the area was not unoccupied at the time. The monument boundaries were further adjusted by other presidential proclamations, then in 1980 the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) set Katmai’s current boundaries and changed its designation to a national park.

The agency tasked with managing the original monument, the National Park Service (NPS), tried to secure funding for a ranger at Katmai but was unsuccessful for many decades after the 1918 proclamation. Only three NPS employees had visited the monument before the NPS issued a concession permit for Brooks Lodge, which opened for business in 1950 at the mouth of Brooks River. Along with the lodge, Katmai’s first ranger arrived that summer.

The original Brooks Lodge was very small and catered primarily to anglers. Beginning in the 1960s, especially after the development of a road leading from Brooks Camp to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, more and more people other than anglers began to visit. This trend continues today. While fishing remains a popular activity, bear viewing and photography have superseded fishing and are by far the most popular activities at Brooks Camp.

A Few Rules

No one knows how many bears lived in Katmai National Monument in the early to mid 1900s, but the population was likely much lower than today due to hunting, fewer salmon in the Naknek River watershed, and the impacts of the 1912 eruption. So few bears used Brooks River in the 1950s that seeing one or even their tracks was a notable event. In the late 20th century, greater protections for brown bears (hunting for example was not permitted in the national monument) likely led to steady increases in the bear population of Katmai and the Alaska Peninsula. In the last 20 years, the number of total independent bears using the river has ranged from a high of 114 in 2009 to a low of 40 in 2016. Last year, bear monitoring staff observed 62 different bears regularly using Brooks River. The increase in bear numbers at Brooks River has led to a changing suite of rules to protect bears.

We often think of park regulations as something intended for human safety, but many, if not most, regulations are written primarily to protect park resources, especially in the case of Brooks Camp. Sometimes the bearcams capture footage of questionable human behavior. Watching this unfold can be stressful and frustrating. However, it’s important to place the behavior of people in context with the park’s rules. (Please also refer to a more thorough summary on the park’s laws and policies page.)

Most national parks in Alaska do not have wildlife distance regulations. Katmai and Denali are the exceptions. Katmai’s wildlife distance regulation reflects a very different tourist economy (most people who visit the park outside of Brooks Camp are guided) and bear population compared to other national parks. It states,

“Approaching a bear or any large mammal within 50 yards is prohibited. Continuing to occupy a position within 50 yards of a bear that is using a concentrated food source, including, but not limited to, animal carcasses, spawning salmon, and other feeding areas is prohibited. Continuing to engage in fishing within 50 yards of a bear is prohibited.

“The prohibitions above do not apply to persons:

- “Engaged in a legal hunt (Author’s note: This is applicable only to Katmai National Preserve; no hunting is permitted in the national park area of Katmai);

- “On a designated bear viewing structure;

- “In compliance with a written protocol approved by the Superintendent; or

- “Who are otherwise directed by a park employee.”

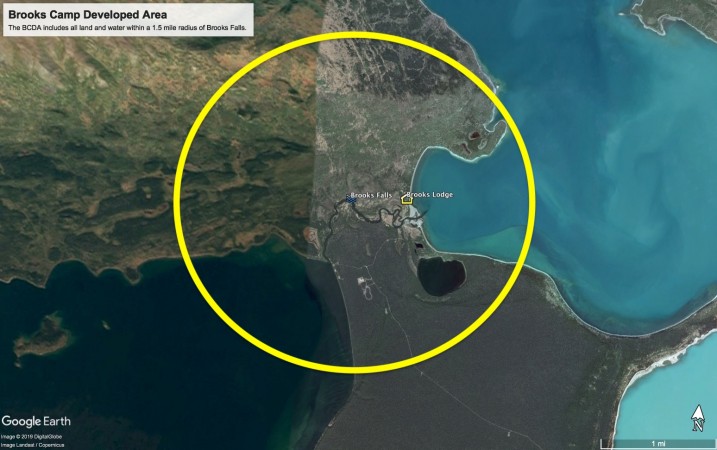

Surrounding Brooks River is an administrative area called the “Brooks Camp Developed Area” (BCDA). This includes all land and water within 1.5 miles of Brooks Falls. Here, a few special rules and regulations apply that go beyond what is required in the rest of the park.

In the BCDA, you…

- Must attend an NPS approved bear orientation immediately upon arrival.

- Can only camp in the campground

- Cannot leave any property unattended outside except for planes, boats, or in specially designated places.

- Cannot have a pet.

- Cannot eat or possess food except inside buildings or designated picnic areas.

In addition to the above, there are two seasonal closure areas at Brooks Camp, both at and near the falls.

- The Falls and Riffles bear viewing platforms and boardwalks are closed from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. from June 15 through August 15. Entering or going upon these platforms and boardwalks during these hours is prohibited.

- The area within 50 yards of the ordinary high water mark of the Brooks River from the Riffles Bear Viewing Platform to a point 100 yards above Brooks Falls is closed to entry from June 15 through August 15, unless authorized by the Superintendent.

Fishing is permitted in the river from June 8 – April 9. The river is catch and release only except downstream of the bridge near the river’s outlet. Downstream of the bridge, you can only keep one fish (of any species except rainbow trout) per person per day. Fish must be immediately placed in a plastic bag and taken to the “fish freezing” building to store in a freezer until you leave. There are no public fish cleaning facilities available. (More information about fishing at Brooks River)

That’s a lot to keep track of, isn’t it? There is also a broader NPS regulation that prohibits “the feeding, touching, teasing, frightening or intentional disturbing of wildlife nesting, breeding or other activities.” This regulation has a lot of wiggle room, especially regarding “other activities,” and rangers must carefully consider when they can enforce it.

Unless something is specifically prohibited, people at Brooks Camp are generally free to explore the landscape as they see fit. Concerns about the behavior or people at Brooks River, particularly if what you see is a clear rule violation, should go directly to the staff of Katmai. At this link you can find contact info. Park staff cannot respond to every instance of someone who appears closer than 50 yards to a bear (frankly, it happens quite frequently and may not be a violation), but they may be able to follow up on obvious and blatant rule violations such as fishing within 50 yards of a bear or entering the closed area at Brooks Falls. Please be sure to include a description as well as the day and approximate time. The email feature doesn’t allow you to attach photos, but if you took a snapshot or video, then please include the link too.

The Future of Brooks Camp

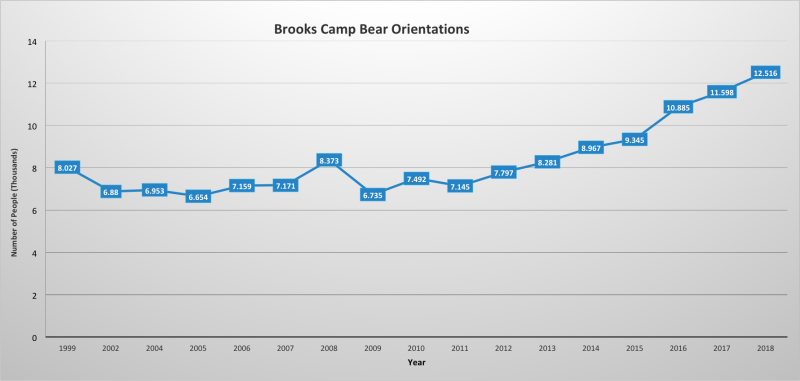

I have been thinking a lot about how to reduce my potential impact on bears when I visit Brooks River. The future of Katmai and Brooks River might look like a lot of other national parks. Climate change will influence the flora and fauna. Certainly, people will continue to visit and likely in increasing numbers. Since 1999, anywhere from 6,500 to 12,500 individual visitors have attended the NPS bear orientation per year with the highest numbers occurring in July. This is a good proxy for overall visitation as everyone* who arrives at Brooks Camp must receive an NPS approved orientation. On the most visited days in 2017 and 2018, over 400 people attended the mandatory bear safety orientation. Including employees and people who stayed overnight, this indicates that more than 500 people are present during the busiest times along the 1.5 mile Brooks River, sharing habitat with dozens of brown bears.

*The exception is specifically approved fishing guides who are permitted to provide the mandatory orientation to their clients. Those orientations are not included in this count.

*The exception is specifically approved fishing guides who are permitted to provide the mandatory orientation to their clients. Those orientations are not included in this count.

What choices should we make to help the National Park Service meet its mission of providing for visitor enjoyment while at the same time conserving the scenery, natural and historic objects, and wildlife of national parks for future generations?

I’ve often emphasized the importance of giving bears space, not only for our own safety but for the welfare of the bears. The regulations at Brooks Camp are designed to reduce the potential for bear-human conflict. Often, it is necessary to make personal decisions that go beyond the rules. For example, the speed limit on a highway may be 65 mph but conditions such as rain, snow, ice, or heavy traffic might require us to adapt to a lower speed. We can think of wildlife distance regulations in the same way. While park regulations permit people to approach a bear as close as 50 yards, that distance may not be appropriate for all bears at all times. Ethical visitation in bear country requires people to be closely attuned to bear behavior and to watch for subtle signs of stress, such as a yawn or the bear changing its intended travel path. These signs are so subtle that they are difficult to detect even at close range and may not be visible at all on the cams.

So what might best practices for bear viewing at Brooks River look like? One evening I sat down and drafted what I call the Brooks River Pledge. It’s a personal pledge between yourself and Brooks River with the goal to emphasize respect for the bears’ space as well as ways to continue to have a high quality bear viewing experience. Please note, this is not official in any way. It does not represent the park or explore.org. Yet, I encourage you to review the pledge and think about applying it toward your wildlife viewing experience at Brooks River.

I also realize that most people do not have the opportunity to visit Brooks River. It’s remote and it’s expensive, so I have also been thinking about those of us who watch the cams primarily. How might you help protect bears, salmon, and Katmai? For one, we can support sustainable fisheries and work to protect the oceans. Katmai’s bear population is highly dependent on salmon. Sustainable fisheries not only support thousands of jobs in the Bristol Bay region but also the health and ecology of Katmai. Our climate is warming and humans are the force driving the change. A warmer and more acidic ocean can also negatively impact salmon. So far the productivity of the Bering Sea and North Pacific have not suffered substantially from climate change, at least in regard to sockeye salmon populations, but we can’t expect that to last under a warming climate. Therefore, it’s important to make sure your elected officials take climate change seriously and are willing to take the steps necessary to mitigate it. We can also make sure our elected representatives knows how much we value parks and urge them to ensure their protection.

An Evolving Place

Like the brown bear who lives as an omnivore but has yet to shed its carnivore ancestry, Brooks Camp as a bear-viewing destination exists within a legacy of development and management set in place decades ago. Watching bearcam, it’s easy to think of Brooks River as a place primarily for bears, yet the river and its bears do not exist in a vacuum. They live and survive in the most visited place in Katmai National Park. The ways in which we use this place continues to change. Through the cams we can experience the abundance of Katmai and consider the challenges of protecting it.

On July 25, 2019, I co-hosted a text chat with moderators and Katmai staff about this topic and history of modern Brooks Camp, bear activity at Brooks River, the meaning of national parks, the future of Brooks Camp, and ethical wildlife viewing. Please review those comments for more information. If you’d like to continue the conversation or have questions about bear and human interactions at Brooks River, please post a comment below.